The Growth Inhibitory Effect on B16F10 Melanoma Cells by 4-BPCA, an Amide Derivative of Caffeic Acid

Article information

Abstract

Caffeic acid (CA) is a phenolic compound found naturally in plants and foods. CA and its natural derivatives are reported to have anti-cancer effects on many cancers, including melanoma. (E)-N-(4-Butylphenyl)-3-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl)acrylamide (4-BPCA) is an amide derivative of CA. Thus far, the anti-cancer effect and mechanism of 4-BPCA in melanoma cells remain unknown. Here we investigated whether 4-BPCA inhibits the growth of B16F10 cells, a mouse melanoma cell line. Of note, treatment of 4-BPCA at 5 µM for 24 or 48 h significantly reduced the growth (survival) of B16F10 cells. On mechanistic levels, treatment with 4-BPCA for 24 h led to the activation of caspase-9/3, but not caspase-8, in B16F10 cells. 4-BPCA treatment for 2 or 4 h also decreased the expression levels of myeloid B-cell lymphoma 1 (Mcl-1) in B16F10 cells. However, 4-BPCA treatment for the times tested did not influence the expression levels of X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP) in B16F10 cells. Of interest, treatment of 4-BPCA for 2 or 4 h greatly reduced the phosphorylation levels of JAK-2 and STAT-5 without altering their total protein expression levels. 4-BPCA also had abilities to increase the expression and phosphorylation levels of glucose-regulated protein-78 (GRP-78) and eukaryotic translation initiation factor-2α (eIF-2α) in B16F10 cells. In summary, these results demonstrate firstly that 4-BPCA has a strong growth-inhibitory effect on B16F10 melanoma cells, mediated via activation of the intrinsic caspase pathway, inhibition of JAK-2 and STAT-5, and triggering endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress.

Introduction

Melanoma is a malignant tumor deriving from melanocytes, and it is considered a rare disease that accounts for 4% of skin cancer cases [1]. In 2022, it is expected by the American Cancer Society that about 99,780 new melanomas will be diagnosed, and 7,650 are expected to die of melanoma in the United States. In the past 10 years, several treatment approaches for patients with localized and or metastatic melanoma have vastly improved. However, these therapies did not manifest a lasting response in most patients [1-3]. Therefore, there is an urgent need to identify or develop new therapeutic strategies for melanoma.

Currently, the cancer treatment strategy of eradicating cells through induction of apoptosis has obtained a lot of interest due to its minimal inflammation reaction [4]. Apoptosis (also called programmed cell death) is one of the cell death types needed to preserve the normal cell turnover with distinctive morphological events such as nuclear condensation and fragmentation, cell shrinkage, plasma membrane blebs, and adhesion loss of the cells [5,6]. It is well known that there are two common types of apoptosis, including the intrinsic (or mitochondrial) and extrinsic (or death receptor) pathways. A wealth of information indicates that the main regulatory proteins in both apoptosis pathways are the caspases [5,7]. There is also accumulating evidence that multiple anti-apoptotic proteins, such as the family of myeloid B-cell lymphoma (Bcl-2) members and inhibitor of apoptosis proteins (IAPs), participate in the regulation of cancer cell survival and apoptosis [4]. Several studies have also illustrated that endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress regulates cancer cell survival and apoptosis [8]. Caffeic acid (CA) is one of the major phenolic acids, which is usually found in numerous natural products, such as fruits, vegetables, olive oil, tea, and coffee [9,10]. Previous studies have reported that CA has a diversity of pharmacological effects, including anti-inflammation, antioxidant, and anti-cancer [11-13]. We have recently used diversity-oriented synthesis to prepare a series of CA derivatives, including (E)-N-(4-Butylphenyl)-3-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl)acrylamide (4-BPCA), and demonstrated their anti-melanogenic effects [14]. 4-BPCA is an amide derivative of CA. However, up to now, the anti-cancer effect and mechanism of 4-BPCA in melanoma are unknown. In this study, we investigated whether 4-BPCA suppresses the growth of B16F10 cells, a mouse melanoma cell line. Here we demonstrated, for the first time, that 4-BPCA at 5 µM has a strong growth-suppressive effect on B16F10 melanoma cells, and the effect is mediated through regulation of the expression and phosphorylation levels of caspase-9/3, JAK-2, STAT-5, GRP-78, and eIF-2α.

Materials and methods

1. Materials

4-BPCA was developed as in our previously published papers [14,15]. All commercial antibodies and chemicals were purchased from the following resources: anti-procaspase-9, anti-procaspase-3, and anti-procaspase-8 were bought from Enzo (Farmingdale, NY, USA); anti-p-STAT-3, anti-STAT-3, anti-p-STAT-5, anti-STAT-5, anti-GRP-78, anti-p-JAK-2, anti-JAK-2, and anti-Mcl-1 antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Delaware, CA, USA); the anti-XIAP antibody was obtained from R&D Systems (MN, USA); the anti-phospho (p)-eIF-2α was bought from Abcam (Cambridge, MA, USA); anti-p-JAK-1, anti-JAK-1, and anti-eIF-2α antibodies were bought from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA, USA), and the anti-β-actin antibody was purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA).

2. Cell culture

B16F10 melanoma cells (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) were grown in DMEM/RPMI-1640 media supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin at 37°C in humidified air (95% air and 5% CO2).

3. Cell count assay and cell morphological analysis

B16F10 melanoma cells were seeded in a 24-well plate. After overnight incubation, cells were treated with vehicle control (DMSO; 0.1%), or 4-BPCA at the indicated concentrations (1, 5, and 10 µM) for different time points (2, 4, 8, and 24 h). The number of surviving cells was counted with the trypan blue exclusion method, which is based on the principle that live cells have intact cell membranes and cannot be stained. Approximately 100 cells were counted in each evaluation. For cell morphology analysis, phase-contrast images of the conditioned cells treated with or without 4-BPCA were taken with a phase-contrast microscope (Nikon Eclipse TS200, Nikon Corp., Tokyo, Japan).

4. Preparation of whole cell-lysates

B16F10 melanoma cells were grown in 6-well plates. After overnight incubation, cells were treated with 4-BPCA (1, 5, and 10 µM) or vehicle control (DMSO) for the designated times. At the designated time point, cells were washed twice with PBS and proteins were extracted using a modified RIPA buffer [50 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 0.25% sodium deoxycholate, 1% Triton X-100, 1% Nonidet P-40, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, proteinase inhibitor cocktail (1X)]. The cell lysates were collected and centrifuged at 12,074 × g for 20 min at 4ºC. The supernatant was collected, and its protein concentration was determined by the bicinchoninic acid assay Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA).

5. Immunoblotting Analysis

Equal amounts of protein (50 μg) were separated via 10% SDS‑PAGE and transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (EMD Millipore) by electroplating. The membranes were washed with Tris‑buffered saline (TBS; 10 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.5) supplemented with 0.05% (v/v) Tween‑20 (TBS‑T), followed by blocking with TBS‑T containing 5% (w/v) non‑fat dried milk. The membranes were probed overnight using antibodies against procaspase-9 (1:2,000), procaspase-3 (1:2,000), procaspase-8 (1:2,000), Mcl-1 (1:2,000), XIAP (1:2,000), p-STAT-3 (1:2,000), T-STAT-3 (1:2,000), p-STAT-5 (1:2,000), T-STAT-5 (1:2,000), p-JAK-1 (1:2,000), T-JAK-1 (1:2,000), p-JAK-2 (1:2,000), T-JAK-2 (1:2,000), GRP78 (1:2,000), p‑eIF-2α (1:2,000), T‑eIF-2α (1:2,000) or β‑actin (1:10,000) at 4ºC, followed by incubation with secondary antibodies conjugated to at room temperature for 2 h. The membranes were washed, and immune reactivities were detected by Super Signal™ West Pico PLUS ECL (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Equal protein loading was assessed via β‑actin expression levels.

6. Statistical analysis

Cell count analysis was done in triplicates and repeated three times. Data were expressed as mean ± SE. The significance of the difference was determined by One-Way ANOVA. All significance testing was based upon a p-value of < 0.05.

Results

1. 4-BPCA markedly inhibits the growth of B16F10 melanoma cells in a concentration-dependent manner

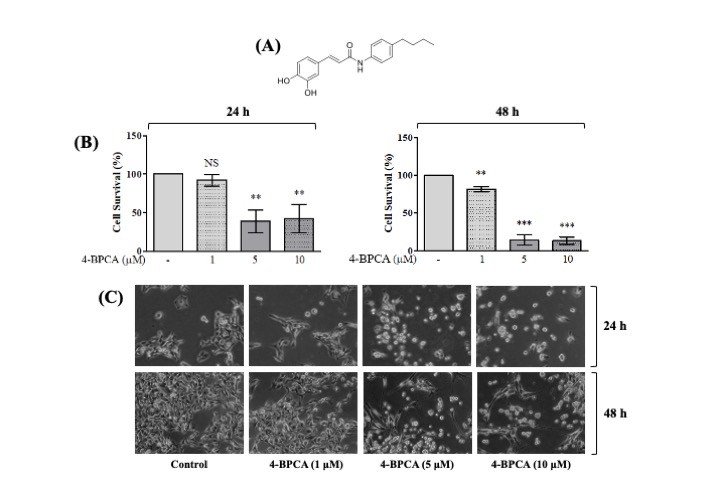

Initially, we examined the effect of 4-BPCA (Fig. 1A) at different concentrations (1, 5, and 10 µM) and times (24 and 48 h) on the growth (survival) of B16F10 melanoma cells by cell count analysis. As shown in Fig. 1B (left graph), compared with control (no 4-BPCA), treatment with 4-BPCA at 1 µM for 24 h did not influence the survival of B16F10 melanoma cells. Of note, 4-BPCA treatment at 5 or 10 µM for 24 h led to a significant reduction of the survival of B16F10 melanoma cells. Moreover, treatment with 4-BPCA for 48 h further resulted in a concentration-dependent reduction of the survival of B16F10 melanoma cells (right graph). Apparently, the maximal growth inhibition of B16F10 melanoma cells was seen by treatment with 4-BPCA at 5 and 10 µM. Microscopic observation further revealed that 4-BPCA treatment caused a concentration-dependent decrease in the number of B16F10 melanoma cells in which the largest reduction of B16F10 melanoma cells was also seen at the 1 and 5 µM of 4-BPCA for 24 and 48 h (Fig. 1C). Due to most strong growth-inhibitory effects on B16F10 melanoma cells, we chose the 5 µM concentration of 4-BPCA for further studies.

Effect of 4-BPCA on the growth and morphology of B16F10 melanoma cells. (A) The chemical structure of 4-BPCA. (B,C) B16F10 melanoma cells were treated with 4-BPCA or vehicle control (DMSO; 0.1%) at the designated concentrations for 24 and 48 h, respectively. The numbers of surviving B16F10 melanoma cells were measured by cell count assay (B). Cell count assay was performed in triplicate. Data are means ± SE of three independent experiments. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 compared to the value of 4-BPCA free control at the times tested. Images of the conditioned cells were acquired by a phase-contrast microscope (C); the magnification rate, 200 ×. Each image is representative of three independent experiments. NS, non-significant.

2. 4-BPCA at 5 µM leads to the reduced expression levels of procaspase-9/3 and Mcl-1 in a time-differential manner in B16F10 melanoma cells

Next, to understand molecular mechanisms underlying the 4-BPCA (5 µM)’s growth-suppressive effect on B16F10 melanoma cells herein, we investigated the effect of 4-BPCA on the expression levels of survival and apoptosis-related factors, such as procaspase-9, procaspase-3, procaspase-8, Mcl-1, and XIAP, in B16F10 melanoma cells over time. As shown in Fig. 2, compared with control (no 4-BPCA), treatment with 4-BPCA for 24 h led to the reduced expression of procaspase-9 and its downstream effector procaspase-3 in B16F10 melanoma cells. In addition, 4-BPCA treatment for 2 or 4 h resulted in a decrease in the expression levels of Mcl-1 in B16F10 melanoma cells. However, 4-BPCA treatment for the times tested did not alter the expression levels of XIAP in B16F10 melanoma cells. The expression levels of control actin protein remained unchanged under these experimental conditions.

Effect of 4-BPCA on the protein expression levels of procaspase-9/3, procaspase-8, Mcl-1, and XIAP in B16F10 melanoma cells. B16F10 melanoma cells were treated with 4-BPCA (5 µM) or vehicle control (DMSO; 0.1%) for the designated time periods. At each time point, whole-cell lysates were extracted and analyzed by Western blotting with corresponding antibodies.

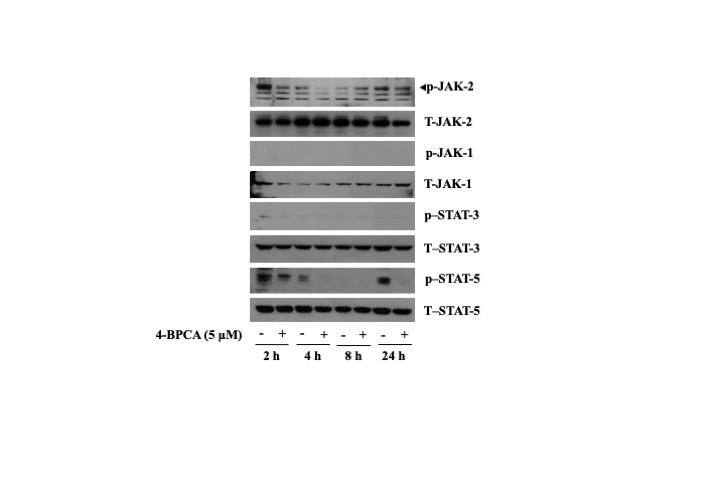

3. 4-BPCA at 5 µM reduces the phosphorylation levels of JAK-2 and STAT-5 in B16F10 melanoma cells

Evidence indicates that the Janus-activated protein kinase-signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK-STAT) pathway regulates cell survival and differentiation [16]. This promptly led us to investigate whether members of the JAK-STAT pathway including JAK-1, JAK-2, STAT-3, and STAT-5 are expressed and phosphorylated in B16F10 melanoma cells, and 4-BPCA (5 µM) regulates their expression and phosphorylation levels in these cells. Notably, as shown in Fig. 3, in the absence of 4-BPCA, high phosphorylation levels of JAK-2 and STAT-5 in a time-differential fashion were observed in B16F10 melanoma cells. However, there was no or little phosphorylation levels of JAK-1 and STAT-3 in B16F10 melanoma cells at the times tested. Strikingly, 4-BPCA treatment at 2 h resulted in a strong inhibition of JAK-2 phosphorylation in B16F10 melanoma cells. Moreover, 4-BPCA treatment at 2, 4, and 24 h led to a strong suppression of STAT-5 phosphorylation in B16F10 melanoma cells. Total protein expression levels of JAK-1, JAK-2, STAT-3, and STAT-5 remained unchanged under these experimental conditions.

Effect of 4-BPCA on the protein expression and phosphorylation levels of JAK-1/2 and STAT-3/5 in B16F10 melanoma cells. B16F10 melanoma cells were treated with 4-BPCA (5 µM) or vehicle control (DMSO; 0.1%) for the indicated times. Whole-cell lysates were prepared and analysed by Western blotting using respective antibody of JAK-1/2, STAT-3, and STAT-5. p-JAK-1/2, phosphorylated JAK-1/2; T-JAK-1/2, total JAK-1/2; p-STAT-3, phosphorylated STAT-3; T-STAT-3, total STAT-3; phosphorylated STAT-5; T-STAT-5, total STAT-5.

4. 4-BPCA at 5 µM increases the expression and phosphorylation levels of GRP-78 and eIF-2α in B16F10 melanoma cells

We next sought to explore whether 4-BPCA (5 µM) regulates the expression and phosphorylation levels of ER stress-related proteins, such as glucose regulated protein (GRP-78) and eukaryotic initiation factor (eIF-2α), in B16F10 melanoma cells over time. As shown in Fig. 4, in the absence of 4-BPCA, there were substantial expression and phosphorylation levels of GRP-78 and eIF-2α proteins in B16F10 melanoma cells for the times analyzed. However, 4-BPCA treatment for 4, 8, and 24 h led to an increase in the protein expression levels of GRP-78 in B16F10 melanoma cells. Furthermore, treatment with 4-BPCA for 4, 8, and 24 h caused an increase in the phosphorylation levels of eIF-2α in B16F10 melanoma cells. Expression levels of total eIF-2α remained constant under these experimental conditions.

Effect of 4-BPCA on the protein expression and phosphorylation levels of GRP-78 and eIF-2α in B16F10 melanoma cells. B16F10 melanoma cells were treated with 4-BPCA (5 µM) or vehicle control (DMSO; 0.1%) for different time points. At each time point, whole-cell lysates were prepared and analyzed by Western blotting using respective antibodies of GRP-78 and eIF-2α. p-eIF-2α, phosphorylated eIF-2α; T-eIF-2α, total eIF-2α.

Discussion

Mounting evidence illustrates that CA and its natural derivatives including caffeic acid phenethyl ester and caffeic acid methyl and ethyl esters has anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and anti-cancerous effects [11-13]. 4-BPCA is a new amide derivative of CA and its anti-melanogenic activity has been recently introduced [14]. However, up to now, 4-BPCA regulation of the growth of melanoma cells and its mode of action are not fully understood. In this study, we demonstrate firstly that 4-BPCA has a strong growth-inhibitory effect on B16F10 melanoma cells, and the effect is mediated through modulation of the expression and phosphorylation levels of procaspase-9/3, JAK-2, STAT-5, GRP-78, and eIF-2α.

Through initial experiments, we showed that treatment with 4-BPCA at 5 µM markedly inhibits the growth (survival) of B16F10 melanoma cells, pointing out its anti-survival effect. Aforementioned, cells undergoing apoptosis have distinctive morphological events including cell shrinkage, plasma membrane blebs, and adhesion loss of the cells [5,6]. Thus, considering the present finings with microscopic cell images that display cell shrinkage and adhesion loss of the cells, it is likely that 4-BPCA may also induce apoptosis in B16F10 melanoma cells. It is documented that apoptosis induction is conducted through two major pathways including the intrinsic (mitochondria-mediated) and extrinsic (receptor-mediated) pathways [17]. The mitochondria-mediated pathway is greatly regulated through cytochrome C release and the resultant Apaf-1-dependent proteolytic cleavage (activation) of caspase-9, followed by the subsequent proteolytic cleavage (activation) of downstream effector caspases such as caspase-3, whereas the receptor-mediated pathway such as death-receptor (DR) is initiated by its receptor superfamily stimulation that leads to the proteolytic cleavage (activation) of caspase-8 [18,19]. In this study, we demonstrated that 4-BPCA treatment at 5 µM resulted in the activation of caspase-9/3, as evidenced by a decrease in the expression levels of procaspase-9/3, but did not trigger the activation of caspase-8, as assessed by no altered expression levels of procaspase-8, in B16F10 melanoma cells. Given that the activation of caspase-9/3 is crucial for the induction of apoptosis, the present findings may further suggest that 4-BPCA treatment induces apoptosis in B16F10 melanoma cells not through the extrinsic pathway but via the intrinsic one associated with activation of caspase-9/3. Mcl-1 and XIAP are known anti-apoptotic proteins [4]. We herein observed that treatment with 4-BPCA lowered the expression levels of Mcl-1 without altering those of XIAP in B16F10 melanoma cells. It is thus conceivable that Mcl-1 down-regulation may also contribute to the growth-inhibitory and/or apoptosis-inducing effects of 4-BPCA on B16F10 melanoma cells.

A wealth of information exists that overexpression and hyperphosphorylation of the JAK-STAT components play important roles in tumorigenesis in solid tumors and blood cancers [16,20-23]. Notably, in the current study, we demonstrated the ability of 4-BPCA at 5 µM to reduce the phosphorylation levels of JAK-2 and STAT-5 in B16F10 melanoma cells. These results point out that 4-BPCA’s anti-survival and pro-apoptotic effects on B16F10 melanoma cells are further attributable to inactivation of this JAK-2-STAT-5 axis in B16F10 melanoma cells.

The ER is the primary organelle in controlling protein folding, translocation and post-translation modification [24]. Multiple lines of evidence indicate that environmental stressors to cancer cells lead to induction of ER stress marked with high accumulation of unfolded or misfolded proteins in the ER [24,25]. It also has been shown that prolonged ER stress is closely linked to induction of apoptosis [26]. GRP-78, is a main chaperone protein in the ER, and is involved in protein folding and assembly of newly synthesized proteins in the ER [27]. Comparably, eIF-2α is another ER-stress marker and also regulates ER stress and/or protein synthesis [28]. It is worthy to note that the phosphorylated form of eIF-2α is an inactive protein that does not participate in the normal protein synthesis [29]. In the present study, we showed clearly that treatment with 4-BPCA at 5 µM led to up-regulation of the protein expression and phosphorylation levels of GRP-78 and eIF-2α in B16F10 melanoma cells. These results indicate that 4-BPCA’s anti-survival and pro-apoptotic effects on B16F10 melanoma cells are further likely to be attributed to induction of ER stress and global translation inhibition.

In summary, this the first study reporting that 4-BPCA, an amide derivative of CA, has strong anti-survival and pro-apoptotic effects on B16F10 melanoma cells, and these effects are mediated through activation of the caspase-9/3-mediated intrinsic pathway, inactivation of JAK-2 and STAT-5, induction of ER stress, and global translation inhibition. Despite the fact that there are still main issues that remain unresolved, such as 4-BPCA’s anti-melanoma effects on animal models, this work suggests 4-BPCA as a lead or candidate small molecule for the treatment of melanoma.

Notes

Author Contributions

YuKyoung Park; Methodology, Data Curation, Visualization, Software, And Investigation. Shin-Ung Kang: Methodology, Data Curation, Visualization, Validation, Investigation. Jinho Lee; Resources. Byeong-Churl Jang; Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts-of-interest related to this article.